Medair South Sudan @ 30

By Steve

The idea of an “emergency” lasting for 30 years is hard to fathom. The circumstances may be a little different

now, but the basic needs are, one suspects, still rather ominously the

same. When we think about humanitarian

emergencies we tend to think of places where armed conflict or natural disaster

have disrupted the normal way of life for people, where infrastructure is

damaged, or where people are forced to leave their lives of relative comfort for

a life of uncertainty. Maybe these last

for a few months or years; enough time to restore some semblance of order once

the crisis has passed.

Imagine a person involved in a car accident. Initially they may require emergency

treatment, but then hopefully they can leave the hospital and continue their

recovery at home.

South Sudan is different, partly because there hasn’t just

been one crisis but many. But also

because it’s never really had a chance to get off the life-support machine in

the first place.

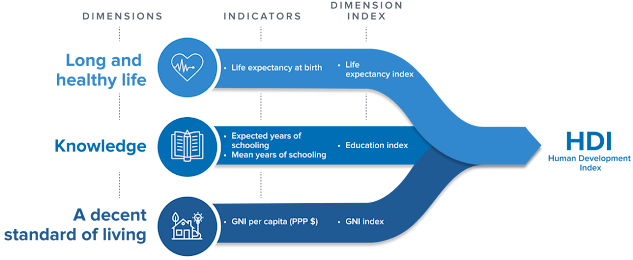

As a country, South Sudan is ranked number 191 out of 191 on

the United Nations’ Human Development Index.

What it needs is development - jobs, schools, healthcare etc. - but investment in these areas are hampered by crises such as civil war, inter-communal

conflict, flooding, etc. So it’s in a

perpetually fragile situation, moving from one crisis to the next, without much

opportunity to move forwards, and hence, a 30 year emergency.

At times it can be difficult to see a way past a time when

humanitarian agencies like Medair are no longer required, and the worry can be

that their very presence is not actually helping in the long run.

But some of the work Medair is doing is, in a small way,

trying to develop capacity within the communities, to lessen the need for us to

come back the next time something goes wrong – ultimately to make ourselves

surplus to requirements.

For instance, in Renk, Medair have constructed and currently support a number of Surface Water Treatment systems. These turn murky, unsafe river water into clean, chlorinated water that is perfectly safe to drink. When these “SWAT”s are first set up, they typically use diesel-powered pumps to suck the water from a river or lake and transfer it into a settlement tank. A second pump is used to transfer the clean water into a storage tank. This isn’t a problem at first, but when the time comes for Medair to leave, it can be challenging to hand over the system to the community because often they either can’t afford the buy the diesel, or it isn’t even available.

So Medair have started to install solar panels and electric pumps that don’t rely on diesel.

In Leer and Pibor, the WASH teams have been rehabilitating handpumps that are located in areas that are prone to flooding during the rainy season, so that they can still be used to get clean drinking water, even if the surrounding area is flooded.

Handpumps draw water up from deep in the ground where it is

protected from contamination from the surface and is therefore safe to

drink. However, if the pump becomes

submerged by flooding, the flood water will get down into the well, polluting

it.

Medair have been building up raised platforms around existing pumps, and installing a new pump a few feet higher off the ground. If the floodwaters come, they will (hopefully) not rise so high that the pump is submerged and therefore, even though it is still difficult to access, when they do people can be sure to get safe drinking water.

In these small ways, our emergency response is also developing capacity in the community. It is a very small step, and there’s a lot more that could (and should) be done, but every long journey begins with those first steps.

Comments

Post a Comment